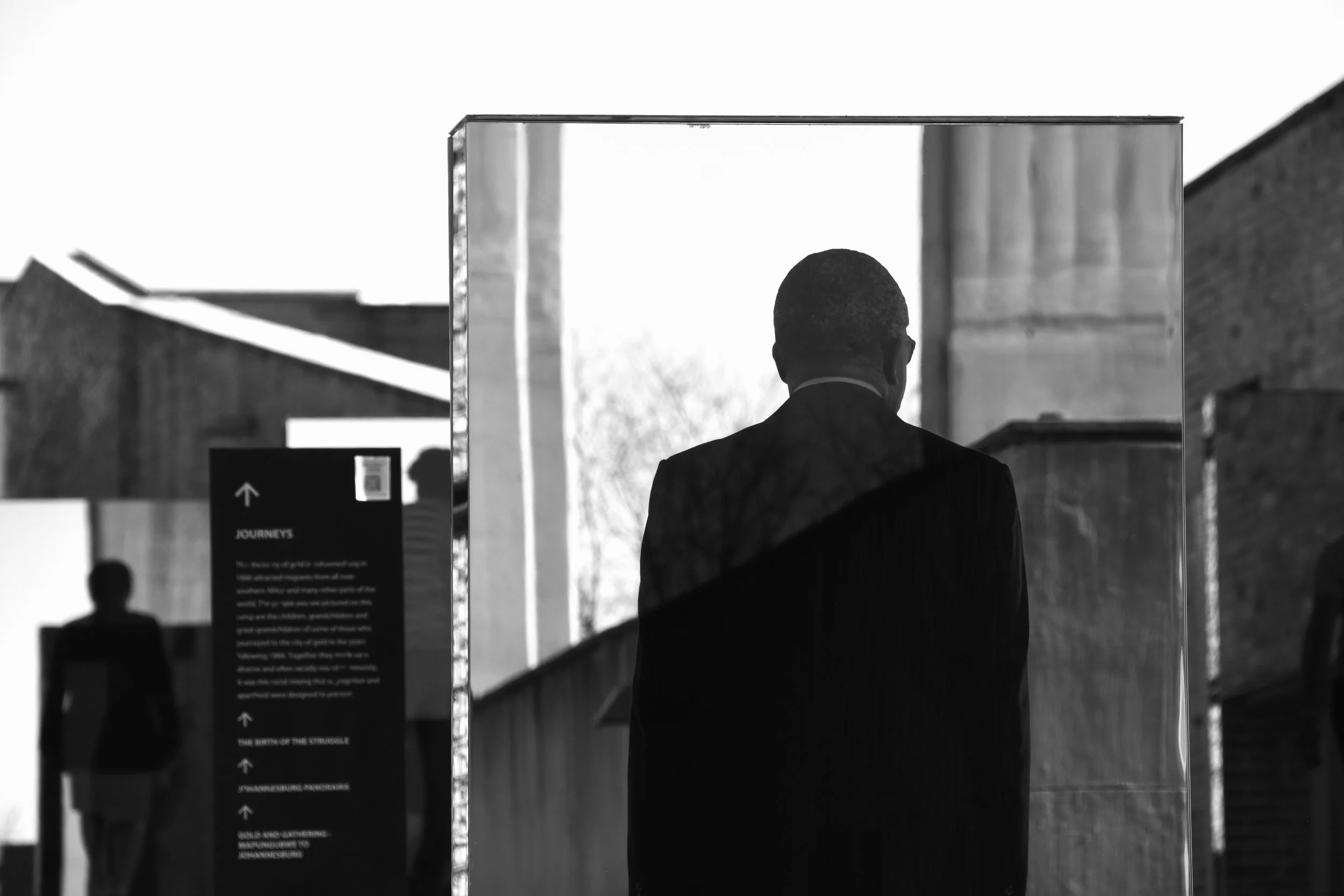

The Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg.

You can’t see a city in a day.

For a place as big as Johannesburg, a day is barely anything – a toe in the pool, a glancing blow, your eyes glued to the window of a moving car, puzzling at what passes.

I was driven to the city’s storied Apartheid Museum by Gilbert, a guide hired from my hotel, who cheerfully pointed out the metropolitan monuments of the city’s skyline – the second tallest skyscraper in Africa, the stadium built for the 2010 World Cup, the remains of a gold mine repurposed into a bustling tourist trap.

With only a brief stopover scheduled in the city, wandering around was not an option – Johannesburg has a rough reputation, and on top of that, it’s geographically unfriendly to pedestrians, with its unfathomably vast size and churning freeways. Asked about the city’s reputation, my driver pointed out (quite reasonably) that there’s no city in the world without bad neighbourhoods. A sense of hungry business brushed up against the car as we past huge, colourful billboards, some advertising familiar brands like Playboy or Nando’s, some alarmingly suggesting that we ought to bulletproof the car.

Johannesburg’s shopping malls are said to be the safest, shiniest parts of the city, but I didn’t have time to look in on the famous locations at Sandton and Rosebank. The one mall I did visit – Eastgate Shopping Centre in Bedfordview – felt relatively safe inside, with security guards stationed at the exits and familiar brand names like Woolworths and Wimpy within, companies long dead back on the UK’s high streets.

We drove by streets of gated houses, compounds surrounded by barbed wire and tall perimeter walls, signs outside boasting of a Neighbourhood Watch equipped for armed response. Stretches of roadside were being licked by flame – through his reassuring patter, my driver told me that the fires were set by workers employed to prune the city’s roadside foliage, who sometimes took to burning it instead – a faster, easier option. Burned grass doesn’t grow back, after all.

*

Johannesburg’s Apartheid Museum

You can’t judge a city in a day, but that’s exactly enough time for judging a museum. Bizarrely, the Apartheid Museum is located on the fringes of Joburg’s sprawling Gold Reef City theme park/casino complex, within a stone’s throw of a roller coaster. Despite this, the museum stands among the best I’ve ever visited – a carefully curated set of historical exhibits aimed to drive home the horrors of South Africa’s past in a way that engages causal visitors and history buffs alike.

Like Germany’s austere Holocaust memorials, great thought has been put into conveying crimes so unbearable the brain might shut down on confronting them. Upon entry, visitors are randomly assigned an ethnic category (black or white, Blankie or Non-Blankie) and sorted into different entrances accordingly. Exhibits range from the enormous form of a full-sized Casspir armoured vehicle, a terrifying spectre of 80s crackdowns, to recreations of the cells where anti-apartheid activists were kept in solitary confinement, to a ceiling of dangling nooses to commemorate those who died in custody.

It's impossible not to be shocked by the bureaucratic horror of apartheid, a racist social system introduced by the South African government in the mid-20th century after previous forms of segregation proved insufficiently efficient in their cruelty. Driven by industrial demand, apartheid was intended to reduce the non-white population to a labour force while simultaneously excluding it from the urban areas most in need of inexpensive labour.

Given this contradiction, it would be easy to view apartheid as a policy doomed to failure. But it endured into the 1990s, inflicting endless indignities, from the demolition of entire non-white neighbourhoods, to the tyranny of the passbook, to chilling policy decisions designed to limit “native” education and push those classified as “Indian”, “Coloured”, or “Black” into a choking hierarchy of permitted ethnic destinies.

Perhaps the system was doomed to destruction by its own short-sighted barbarism. But as the museum makes very clear, countless hours of suffering were accrued under it – and without opposition, it would have likely been amended to accumulate countless more.

*

Johannesburg’s skyline - views from around Constitution Hill and the Apartheid Museum.

On the car ride back from the museum, I asked Gilbert if he had any thoughts on the country’s current politics, expecting he might cheerfully evade the question (I would, in his position). He pointed to a stretch of road and told me that if people were upset with it, they would fill the road in protest, and demand the government fix it. He said that while South Africa had its problems, thanks to Nelson Mandela, the people were free.

You can’t do much with a few hours in a city. But if you’re ever in Johannesburg, I highly recommend a visit to the Apartheid Museum. It’s best to consult a proper guide, tour group, or driver through your hotel – the city isn’t convenient or safe to wander. But the museum is certainly worth a visit, even if you’re only in town for a day.

Plus, there’s a landing pad opposite the museum where you can charter helicopter rides (weekends only, not cheap at all, consider at own risk). For anyone visiting with deeper pockets – and more time – than I.

Outside the Apartheid Museum.

Footnotes:

The museum was built by Gold Reef City as a condition of its gambling license, a business created by two brothers who made their fortune selling apartheid-era skin lightening cosmetics. Even museums are not free of history – though the Apartheid Museum nevertheless manages to impress thanks to its sombre and unflinching design.

If you can wrangle a second day in the city (which I eventually managed), the prison museum on Constitution Hill is also worth a visit.

Offering a similar experience to the Apartheid Museum, it lays out the horrors of the city’s prison for black men, as well as the former Boer fort used to house white prisoners (and on occasion Nelson Mandela), and the Women’s Jail which incarcerated prominent anti-apartheid figures such as Fatima Meer and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela.

Tours circulate Constitution Hill every hour, with longer and more detailed tours leaving at 10am and 1pm respectively. The ramparts of the Old Fort also offer impressive views of the city, including the bustling Central Business District, which it is very not advisable for tourists to wander unguided.

Signage in and around Johannesburg’s Constitutional Court, built amid the remains of the old segregated prisons. The slogan “A Luta Continua,” emblazoned in neon lights inside the court, is Portuguese for “The Struggle Continues.”

The phrase is a sculpture by Thomas Mulcaire, symbolising the continuing nature of the struggle for justice and equality.