Brooklyn

When JFK contacted me to say they’d found my luggage, I was up there like a shot.

Losing your backpack is a huge blow, especially when it's your own fault. Flushed with jet-leg and New York excitement, I'd accidentally taken the wrong bag home from the airport (I know), and it had been up to the staff at Norwegian airlines to save the day.

It took a day and a night for my bag to be found, leaving me to contemplate life without a toothbrush or clean underwear. When my bag was finally unearthed, it meant a midnight expedition to the airport to retrieve it.

Riding back from the airport in a taxi, clinging to my salvaged baggage, I realised that my New York taxi driver had--despite his protests otherwise--become very, very lost. This was not the neighbourhood of my hostel. We were driving in circles through a dark mess of shuttered shops and squat apartments, somewhere near Brooklyn. There was a gas station on the corner, splashed with red and white lights. Police cars were crowding under the gas station's neon roof. A circle of officers huddled around a man lying prone on the tarmac, in a puddle of dark liquid.

'Oh shit,' said the taxi driver, in broken English. 'There’s been a shooting there.'

***

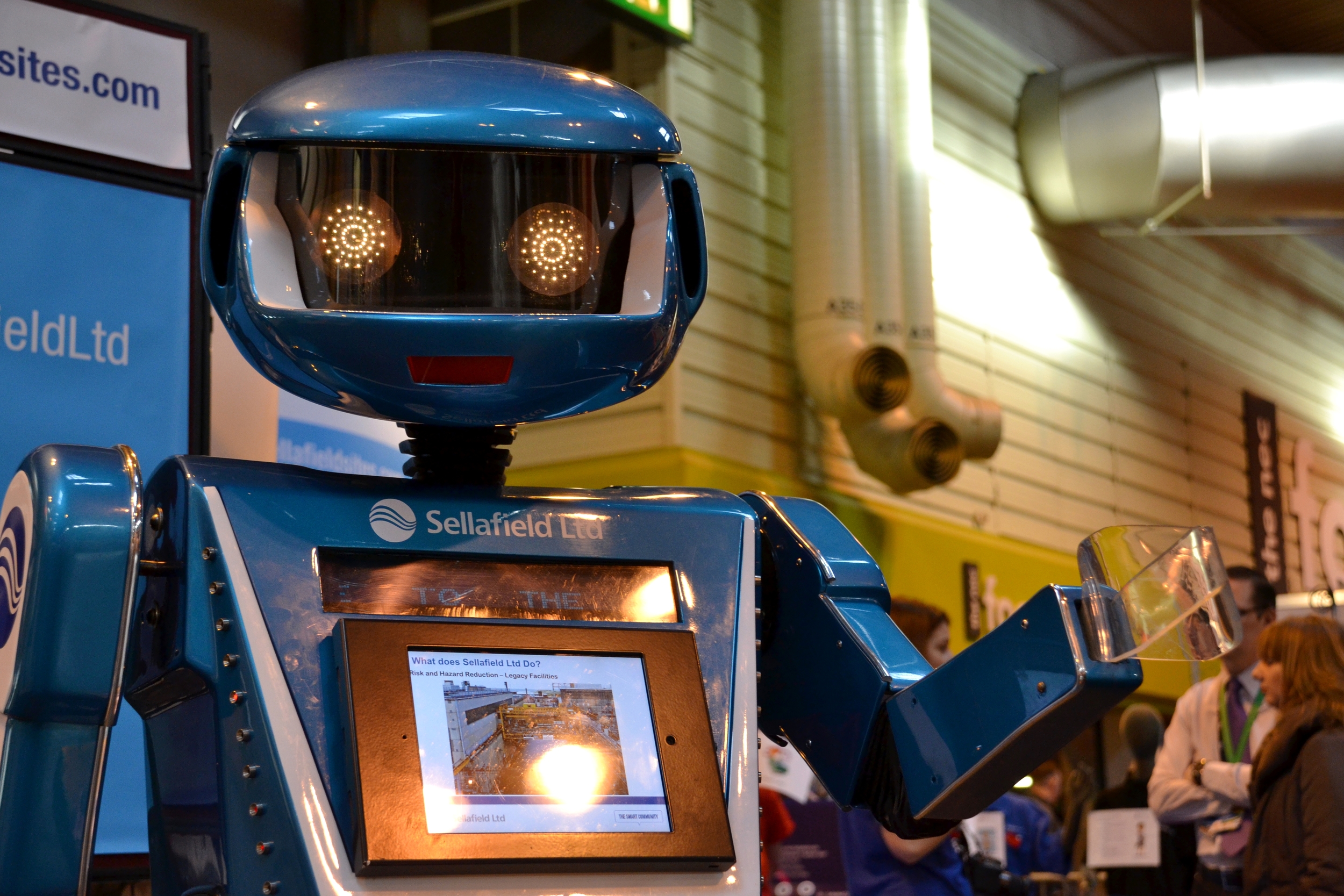

Street art in East Williamsburg, Brooklyn

***

Apparently, the neighbourhood I'm staying in used to have a lot of crime.

Not anymore. I'm in a hostel in East Williamsburg--one of the trendiest, most up-and-coming parts of Brooklyn. By day, the area looks off-puttingly like industrial district. It's filled with squat warehouses, loud with the patter of construction, crowded by cement trucks lumbering along wide streets in small herds.

But look carefully amid the noise, and you'll find plenty of colour. The whole neighbourhood is filled with graffiti, fresh art dripping from the walls. By Morgan Avenue, the local subway station, people are selling second-hand books and VHS videos, piled on little stalls. Unassuming doors in the graffitied walls lead into trendy cafes, crowded with young people sipping on ice tea.

Come night, the industrial district gives way completely. The cement trucks slink away, and bars and restaurants open. Amid empty warehouses, little canopies unfurl, thick with fairy lights and coloured bulbs. Artists spill out of basement galleries, chatting on the sidewalk. A van on a street corner sells vintage clothes well into the night. The New York hipster crowd comes ambling out to play.

Bohemian is the word, I think.

***

Hipsters love their vinyl records.

***

‘In the late 90s, early 2000s, this place was desolate,' a man named Mike told me, on my first day in the neighbourhood. Mike was a big guy with a belly lounging in its vest, wearing a frazzled beard and a necklace heavy with glittering trinkets--fragments of rock and metal. He was an artist, and a pretty good one at that. ‘Drugs, crack, hookers, everything,' he added, recalling the old version of East Williamsburg.

We sat together in a street-corner park, watching kids play in the sweltering sun; basketballs bouncing between groups of teenagers, predominately black. 'Now it’s the place to be,' Mike mused, 'it has an energy, you can feel it go when you leave the area--it’s spiritual.'

Nearby, a friend of Mike's was darting around the park, wrestling with the multiple cameras around his neck. Named John Isaac, he was once a photojournalist for the United Nations (not to mention a personal photographer for Michael Jackson). Now retired, John has found he can't stop taking photos of New York city streets.

'My wife is always saying to me,' John told me confessionally, between snaps, 'you're 73 fucking years old, you're not a young man anymore.' But John can't help it; everywhere he goes, he sees new photos that need taking.

John Isaac, unstoppable photographer.

Mike and John share an art studio together in Yonkers; another once-rough neighbourhood that’s slowly creeping into vogue, with old factories and warehouses becoming studio apartments for artists. East Williamsberg is a little further along the same evolution; it's well into courting gentrification, but still feels abuzz with underground energy. It's the perfect place for people like Mike and John to come for urban inspiration.

They were friendly conversationalists, perfectly willing to start chatting with a perfect stranger like myself. But then, it's that kind of area.

A little later in our talk, Mike drifted away from the topic of the neighbourhood and started explaining how evolution didn't happen, and how the world is secretly run by a shady cabal of shadowy figures, intent on stymieing human spiritual potential. He lit a cigarette that wasn't filled with tobacco, and became impassioned on the subject.

I found that part of the conversation a little hard to track. Nearby, John Isaac shook his head ever so slightly, and began earnestly advocating for evolution; a gentle debate pinging back and forth between them.

That's the thing about Bohemia, I guess.

You're hear all sorts of things.